With its long-term nature and relatively high income, real estate is appropriate for pension funds. Real estate will continue to receive a share of investment capital from this group.

Institutional capital is capital invested on behalf of others, or beneficiaries. Public REITs, insurance companies and other investment firms, governmental entities, endowments and foundations and, of course, pension funds, represent institutional capital.

Beneficiaries include shareholders, recipients of gifts from endowments, and retirees. All are active in real estate ownership but some of the largest investors are pension funds with responsibility for employee retirement assets.

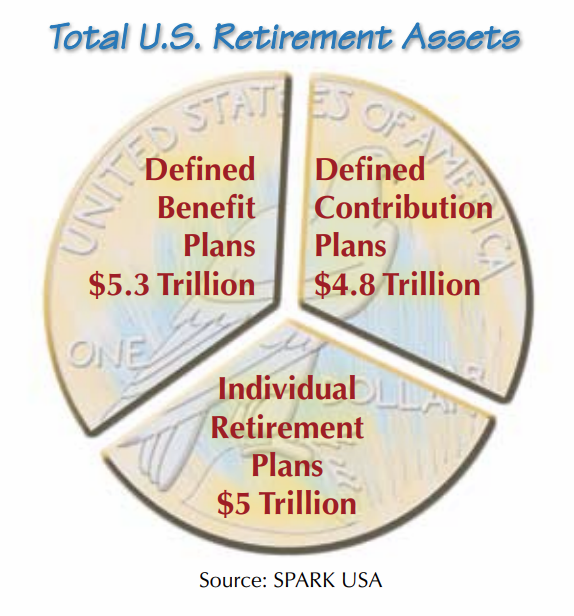

Retirement assets are categorized as corporate and public (governmental) defined benefit plans and defined contribution plans such as IRAs and 401k or 403B plans. Total retirement assets in the United States as of December 2009 were estimated to be about $15 trillion (see figure).

Defined benefit plans include retirement assets of government employees and corporate employees, the oldest group of funds. As many corporate plans have been converting to self-directed or 401k plans, liquidity is a concern, and real estate is not a large component of asset allocation.

In stark contrast, government plans (also known as “public” plans) continue to see asset growth. Some of the largest of these are international, such as Government Pension Investment of Japan, but these should not be confused with sovereign wealth funds such as the Government of Singapore Investment Corporation or the Kuwaiti Investment Authority.

Birth of Pension Funds

The earliest pension funds were started before the 20th century by the railroads. As workers began to live longer, societal norms shifted, and retirement schemes were designed to encourage older workers to retire by providing monthly annuities. Then, younger and theoretically more productive workers could take their place. Unfortunately, many abuses were recorded, and retirees often never saw the benefits promised.

Throughout the 20th century, Congress enacted legislation designed to safeguard pension assets. The culmination of these laws was the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) passed in 1974.

ERISA mandated many standards including rules on disclosure and funding. The most important aspect for real estate was the requirement for diversification. Modern portfolio theory also encouraged diversification as an essential investment practice. In essence, fiduciaries were ensured that an investment in other asset classes besides stocks and bonds was okay.

Inflation in the 1970s eroded the value of bonds, making hard assets such as real estate even more desired as investments. Ultimately, the combination of real estate’s relatively good real returns and academic and legislative support set the stage for billions of dollars to flow into real estate.

Real estate has historically been favored by high-net individuals or controlled by the state. Even the term “real estate” derives from the French word real (royal). From royalty to industrialists, real estate was a source for creating or maintaining wealth, but few companies could invest on behalf of others.

Institutional investment is a recent phenomenon, becoming an option for insurance companies after World War II. Life insurance companies were among the first to discover that real estate’s long-term income stream was a perfect fit for their long-term liabilities.

Until the 1970s, pension funds had no experience with real estate investments. Even today, funds often have minimal staffs managing hundreds of millions or even billions of dollars.

After passage of ERISA, there were only a few real estate funds available for pension funds to consider. Most of these early funds were sponsored by life insurance companies or commercial banks. In 1968, Wachovia Bank and Trust started a commingled fund for pension funds, but the Prudential Property Investment Separate Account (PRISA) was by far the better known fund.

For decades, PRISA was the largest and best known of all institutional funds. Started in 1970, fundraising went slowly, but then interest began to accelerate. Most investment was either done through these commingled funds, which are similar to a partnership, or separate accounts that benefit only one fund.

The number of real estate investment advisors accelerated in the 1980s. According to Bernard Winograd in his 2001 article “Pension Funds Still Crazy,” there were at the beginning of the decade approximately 15 firms capable of providing advice to pension funds. By the end of the decade, more than 75 firms existed. Early successes led to greater interest and, hence, expansion. Even so, by 1991 two of the largest firms providing real estate advisory services were the insurance giants Equitable and Prudential.

The ensuing crash of the late ‘80s was well documented, and pension funds suffered poor returns along with other real estate investors. Fund managers’ greatest frustration was the lack of warning from their advisors that difficult times were ahead after 1987. The poor returns caused pension funds to re-examine everything about real estate investments, from the rationale promoting real estate as a solid investment to the structures used by the advisors.

While the rationale ultimately survived, pension funds demanded changes to compensation arrangements to reduce inherent conflicts of interest. Because real estate advisors were paid fees only on assets under management (AUM), there were few incentives to sell assets when appropriate. In addition, advisors reported values at the highest possible levels to maximize their fees.

The typical fee structure would provides a percentage of fees on AUM to cover overhead but allows the real estate advisor to receive a percentage of the “profit” upon sale of the property or liquidation of the entire fund. It allows a 2 percent base fee plus 20 percent of the profit as defined. This restructuring results in advisors making substantial profits upon final liquidation of the portfolio as they participate in the realized gains through carried interests or “promotes.”

These compensation structures were taken from the private equity industry, which includes leveraged buyout and venture capital funds. The design encourages the alignment of interests with the manager and its investors.

Suddenly, real estate caught the interest of Wall Street firms, including investment banks and traditional private equity firms. Further borrowing from the private-equity world, funds were marketed as core, value-added or opportunistic in an attempt to explain increasing risk-reward strategies (see Center publication 1849, “Private Equity,” for further description of these funds.)

Starting in the late 1990s, pension funds again increased allocations to real estate. The cycle of failed returns repeated. This time, the culprit was not overinvestment in new real estate products (oversupply from development) but the extreme leverage used worldwide by the investment community and consumers alike.

Despite the bad outcome (returns are estimated to have fallen by as much as 40 percent from their peak), pension fund managers still are interested in real estate. The reasons never change: poor return expectation for other investment opportunities, diversification and concerns about inflation. In addition, many funds believe the timing of investment may be favorable. The continued interest at the moment has led to continued capital availability favoring particularly high-quality real estate assets (Table 1).

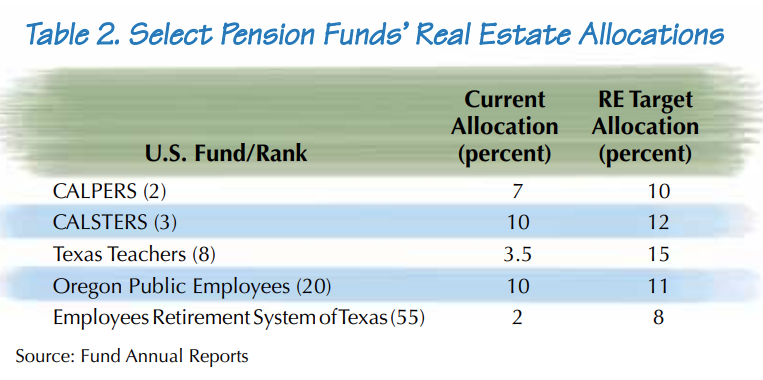

Determining the appropriate amount of funds to invest in real estate is done using a portfolio optimizer. Most models suggest a 5 to 15 percent allocation to real estate is appropriate. So if a fund has assets of $15 billion, a 10 percent allocation to real estate would suggest $1.5 billion of capital available for real estate investment.

Most pension funds have yet to achieve their targeted allocations and actually have fewer real estate assets as a percentage than desired (Table 2). This is another reason why interest in real estate has not waned despite recent poor returns.

Finally, it is important to realize that pension funds have a time horizon that is very long — usually 30 years. They can afford to be slow and deliberate in their investment strategy. Given all of the inherent needs of a plan, pension funds’ interest in real estate investments can be expected to continue for the foreseeable future.

Donnell ([email protected]) is executive professor of finance and director of real estate programs in the Mays Business School at Texas A&M University.