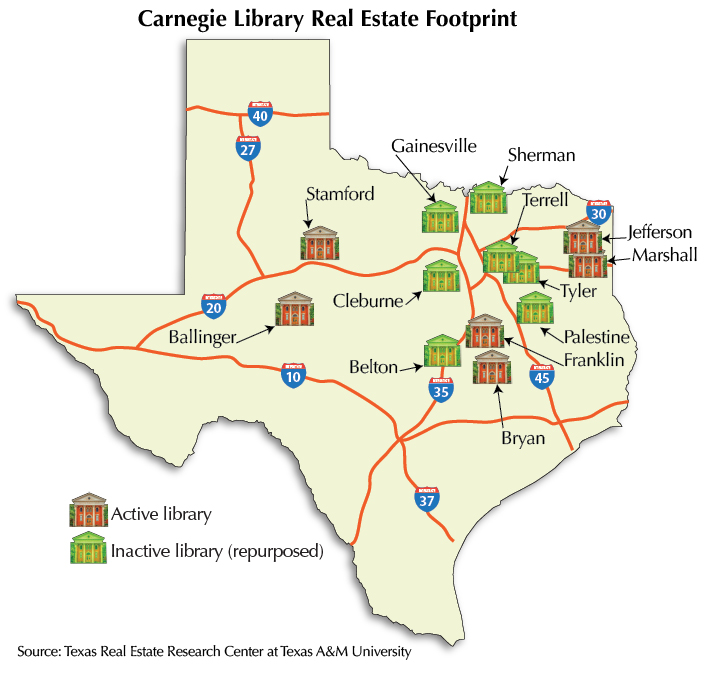

- Of the 1,700 Carnegie libraries built in the U.S., 32 were in Texas. Of those still standing, four are lending libraries while one is now a historical research center.

- The Carnegie History Center in Bryan houses historical materials for research both onsite and digitally.

- The center aids in preserving architectural heritage, fostering economic growth, and revitalizing downtown areas.

It’s one of the most distinctive buildings in Downtown Bryan. With its neoclassical-revival-style red brick, tall windows, white exterior finishes, and four tall columns climbing the height of the two-story building, it’s certainly the most distinguished looking.

Just inside the double-door entrance are two narrow wooden stairways—one to the right, the other to the left. About ten steps ahead is the central help desk, the heart of the first floor. The space surrounding it is cozy in the best possible sense of the word. Except for a couple of large study tables and some chairs, the entire floor is packed wall-to-wall, floor-to-ceiling with books, photos, art, and historical artifacts, many relating to real estate in the region. Upstairs is more of the same. The building smells pleasantly of old wood and even older books. The atmosphere is conducive to the building’s intended purpose: historical research.

Welcome to the Carnegie History Center.

Originally the Carnegie Public Library, the building is now a repository for rare historical materials (although the name on the structure has not changed). The center’s holdings are astonishing. They include family Bibles, old court records and school records, countless photos and maps spanning the early 19th century through the 20th century, and collections of documents donated by some of the city’s founding families. Some materials document aspects of the area’s history that are unpleasant but no less important. For example, the center has a zoning map from the ’50s showing how schools were segregated and original bills of sale from the slave trade (one written on what appears to be stationary from a London hotel).

Armed with such a rich treasure trove of documents (plus a little time and a lot of patience), even the most amateur history buff could piece together a respectably detailed history of the Brazos Valley, its real estate, and its people. That’s why the library’s resources are used largely for genealogical research.

Largely, but not entirely.

Carnegie History Center Branch Manager Rachael Altman recalls helping a woman in need of documentation to resolve a land dispute.

“She was Italian and had land that goes back several generations,” Altman said. “She came here to do land research for a contested ownership dispute. I think the previous owner had passed away and didn’t leave a will or enough documentation. We were able to help her establish the genealogy of that particular piece of land through all of our records and maps.”

As a gesture of thanks, Altman said the woman treated the staff to a homemade lasagna dinner. History has never tasted so good.

The history center’s uses for real estate extend even further, though, potentially serving as a tool for economic development in the Brazos Valley. The library’s onsite and online resources can help with the restoration of historic homes and even downtown renovations, and studies have shown that heritage-related tourism can mean big business for smaller communities. More on that later.

THE MORE THAN 120-YEAR-OLD Carnegie Public Library building in Bryan is the state’s oldest functioning Carnegie library. Now a historical research center, its holdings include documents that have aided the area in preserving historic buildings.

Carnegie’s Legacy of Learning

Established in 1903, the Carnegie History Center was originally a lending library, one of around 2,800 built by Scottish-American steel magnate and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie from the 1880s through the 1920s. He donated $40 million toward the libraries globally (roughly $1.3 billion in today’s dollars), bringing history books and literature to millions of people who otherwise wouldn’t have had access. A highly regarded writer himself, Carnegie once wrote, “A man who acquires the ability to take full possession of his own mind may take possession of anything else to which he is justly entitled.” His libraries were a testament to that.

Almost 1,700 of Carnegie’s libraries were in the United States, and 32 of those were in Texas (see map). The first Texas library was built in Pittsburg (Camp County) in 1898. Construction of the Bryan library began in 1902 with a $10,000 donation from Carnegie, a sizeable amount at the time.

Most of the Texas libraries are no longer standing, while some have been repurposed. Of the five still operating as libraries, the one in Bryan is the oldest. However, it served as city office buildings starting in the late ’60s before reopening in 1999 as a special collections library and genealogical research center.

FROM THE LIBRARY’S HOLDINGS: Clockwise, Bryan’s Main Street (circa 1900), Cavitt House (circa 1875), original Brazos County Courthouse building plan (1st floor), and Original Bryan School (circa 1880).

Giving History a Home

These days, Altman said they keep their doors open and the lights on mostly through funding from the City of Bryan.

“We also apply for various grants, and we receive generous donations from patrons and through the Friends of the Library,” she said.

While funding isn’t an issue, finding documents, maps, photos, and other artifacts can be. It often depends on good luck and great timing.

“We’ve seen people who work in community buildings putting boxes of old documents by the dumpster or loading them into their car,” Altman said. “There was this lovely local group called the Brazos Genealogical Association that saved court records dating back to the 1820s from the dumpster.”

Some of the library’s most important historical documents came from individual donors and local groups. For example, a collection of Bryan City Council minutes—including old leases, deeds, agendas, maps, and plats—was donated by the late Dr. Paul Van Riper, former head of Texas A&M University’s Department of Political Science and founder of the Citizens for Historic Preservation. The Citizens for Historic Preservation also donated the Cavitt Collection, named after one of Bryan’s earliest and most prominent families.

“When we reopened back in ’99,” Altman said, “we put out a call to the community asking for any historical books and photos they thought would be good additions here. People were finding things at estate sales and sending them to us.”

Then there’s the matter of making materials available in a format that preserves the documents. Visitors can browse the center’s shelves of books, but some of the more delicate documents can be viewed only via microfiche. A few years ago, the center began digitizing its collections to make them available online, a process that relies on the center’s small staff and a group of volunteers and will take considerable time to complete.

Although the Carnegie History Center’s collections are specific to the Brazos Valley, they partner with other major public and university libraries around the state. They also provide users with access to extensive online resources that might be out of the price range of many organizations and individuals.

“Newspapers.com is an amazing resource for digging up old articles and photos from just about everywhere, but it can be expensive. You can access it for free at our library,” Altman said. Other online resources available through the center, as well as at other public libraries, are Texshare.net and Newsbank.com. Ancestry.com is another big draw for the center’s in-house patrons.

How History Can Boost a City’s Economy

The vast resources of Carnegie and other public and university libraries are useful to individuals hoping to put together histories of their families and heirloom properties, but they can also prove invaluable to cities in preserving historic buildings and even restoring whole neighborhoods. This potentially means economic growth for communities, as shown by downtown revitalizations that have occurred across the state over the past 30 or so years (for more on this read “This Old Loft: Downtown Living in Small Town Texas.”).

The Texas Historical Commission (THC) commissioned a study of the economic impact of historic preservation. Conducted by the University of Texas and Rutgers University, it’s one of the earliest and most comprehensive studies ever done on this topic in the United States (conducted in 1999 and last updated in 2015).

The study concluded that “more than 10.5 percent of all travel in Texas is heritage-related, and that number continues to rise. Heritage tourists contribute more than their share to spending, $7.3 billion or about 12.5 percent of total visitor spending in Texas.”

In addition, according to the report, “private property owners invest almost $741 million annually in rehabilitation of designated historic buildings, more than 7 percent of all building rehabilitation activity. Public entities add at least $31 million for a total annual historic rehabilitation investment in Texas of approximately $772 million.”

The THC says historical designations can help qualify property owners for grant funding or tax incentives.

Meanwhile, as of 2015, THC’s Texas Main Street Program has helped 89 downtown districts with revitalization efforts, producing an average of $310 million annually in state GDP.

Cid Galindo and Dr. Steve Wiggins recognized the importance of a vibrant downtown district—and the role history plays in restoring that vibrancy—back in 1986 when they proposed a comprehensive revitalization plan for Downtown Bryan.

“It is the common historical heritage of Bryan that appeals to the widest possible socioeconomic range of the community,” they wrote. “The sense of historical continuity weaved into the bricks and sidewalks of Main Street is the single most important asset downtown has.”

Having a building receive a historic designation requires not only a thorough knowledge of its history, but documentation verifying that history. The minimum age for a building to qualify and receive a plaque is 50 years.

“If you have proof that, say, a senator drafted a piece of legislation while staying on the property, it definitely helps build your case to be granted the designation,” Altman said.

And, of course, earning a historical plaque also means restoring a building to its original condition.

“To do that,” Altman said, “every architectural detail must be right.”

She said old photographs and even original architectural sketches archived at the center have helped with the restoration of numerous well-known local landmarks, including some downtown. Owners of the Astin Porter House, Cavitt House, and Milton Parker B&B, several of the city’s most iconic historic homes, have also turned to the center for assistance with their restoration efforts.

Changing Lives, Reviving Communities

Historical preservation is about much more than fixing up old buildings. It’s about finding a building’s story, weaving it into the fabric of the region’s history, and sharing it with the world.

Those stories, even if they’re 100 years old or older, can change lives today, whether by helping someone retain a piece of land that’s been in the family for generations or by putting a forgotten neighborhood—or even an entire town—back on the map.

“Buildings and land are a lot like people,” Altman said. “They have their own stories to tell. We help them tell it.”

_______________

Bryan Pope ([email protected]) is senior editor with the Texas Real Estate Research Center.

In This Article

Contents

Key Takeaways

You might also like

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR

Publications

Receive our economic and housing reports and newsletters for free.